Triumph and trauma: ADT's 50 years

Fifty: Half a century of Australian Dance Theatre

Written by Maggie Tonkin

RRP $75

FIFTY years and five artistic directors (eight if you include the interim directors): Australian Dance Theatre is possibly not just the oldest contemporary dance company in Australia but also the most turbulent. The Adelaide-based company has a history of tossing out artistic directors at short notice, to devasting effect. And yet, as author Maggie Tonkin writes in her introduction, “the acrimonious dismissal of four out of its five artistic directors, has had both negative and positive effects. Obviously, each dismissal has been profoundly traumatic to the people concerned . . On the positive side, despite these traumatic ructions, the repeated changes in artistic director have established the paradigm of stylistic renewal that has become ADT’s trademark”.

Fifty has been commissioned by ADT to celebrate the company’s golden anniversary and “its purpose is not to settle old scores but to celebrate the work of Australian Dance Theatre”, Tonkin writes. The focus is not on the dismissals (though these are unavoidable) but equally on the artistic contribution of each director, offering fascinating insights into their approach to their responsibilities as leaders of the company, as well as their personal creative instincts and choreographic methods. Each artistic director is given his or her own chapter, including the short-term interim directors.

Founder Elizabeth Cameron Dalman tells her story in her own words. In 1965 dance in Australia mostly meant classical ballet, and Dalman was a genuine pioneer. She set what was to become a tradition of incredible drive and passionate commitment by all the directors, determined as she was to introduce her discoveries of contemporary dance (particularly those taking root in America) to Australia and encourage the development of a local contemporary dance. With little in the way of government funding for the arts at that time, she built up audiences and dancers through her own hard work, through contemporary dance classes, audience education programs and constant touring. Her dismissal 10 years later by the “new board” seems the rudest of all, given that she was the person who owned the company. But it was to be just the start of similar behaviour by the ever-present, mysterious “board”, whose reasoning we never discover.

Jonathan Taylor is the next one to take the reins, moving his family from the UK to take up the invitation. He enjoyed a huge leap in funding, which included a period when the company received money from the federal, SA and Victorian governments. He introduced a more European/UK focussed, “neo-classical” style (though it is pointed out that this description does not do justice to the variety of the repertoire). He enjoyed many commercial and popular successes but, by 1982, the company was struggling financially – so much so that the “ADT board sent Taylor to Sydney to meet secretly with Graeme Murphy to discuss merging the two companies”. The Victorian government’s decision to end its contribution spelt the beginning of the end, and Taylor was given his marching orders in 1985.

Following a year under interim artistic directors Lenny Westerdyke and Anthony Steele, Leigh Warren was the next to take the lead. Under his direction the company once steered back to “ a purely contemporary ensemble as had been envisioned by founder Elizabeth Cameron Dalman”, and to the fostering of Australian artists. Within a year he turned the company’s $90,000 debt into a $23,148 surplus. From the beginning he specified that he would “create no more than two works per year, since his primary role would be to commission works from Australian choreographers . . . By 1991 he had commissioned 28 Australian dance works, built up a cogent ensemble of dancers and impressive repetoire while keeping up the “company’s tradition of extensive regional touring” but the board once again was dissatisfied and told him his contract would be shortened by a year.

Possibly the stormiest period was under Meryl Tankard (1993-1996), whose dismissal received a huge amount of coverage in the press. Under her the company changed direction toward a more “dance-theatre” style, one she had inherited during her time as a dancer with the Pina Bausch Tanztheater in Germany. Tonkin’s account includes an interesting description of her choreographic process. Tankard’s vivid and theatrical repertoire was utterly unique in Australian dance and soon earned her a impressive national and international profile and a passionate following. But the board intervened one more and dissolved Meryl Tankard Australian Dance Theatre (as it had become known) “. . . an act even more incomprehensible because Tankard was a choreographer of international repute at the peak of her career, whose company was in demand worldwide”.

Bill Pengelly directed the company for a year in 1999 and, it is revealed here, hoped that his position may become permanent. Instead, the current director Garry Stewart, was appointed, where he remains to this day, an unusually long period. The stability of his tenure can be attributed in part to a differently structured board (follwing a review after Tankard’s dismissal), which went from its beginning days of being almost entirely of government appointed members to one in which “the company could appoint seven members, with the artistic director having the right to also take a seat.”

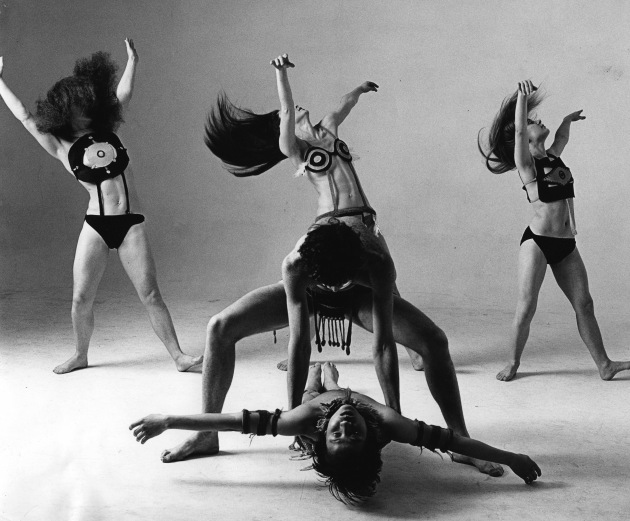

Author Maggie Tonkin is a lecturer in the English Department of the University of Adelaide and regular contributor to Dance Australia. She has managed to draw together what must have been huge and emotionally charged history into a fluent, concise and very readable account. The book is an elegant hard cover, square format, and generously illustrated with beautiful photographs from all periods, all of which are meticulously captioned down to the last dancer.

Fifty is a valuable contribution to our knowledge of Australian dance history. It is all the more precious for putting on the record all directors’ accounts while they are still alive and kicking.

Onward to another Fifty!

- KAREN VAN ULZEN