Annually from December to March, sleepy dancers on German long distance trains are a common sight.

These well-travelled creatures are easy to spot on their way to auditions, stretching in their cushioned seats, comparing outfits and brushing their hair often before the sun has risen.

This is not a uniquely German phenomenon; it can be seen in many West European countries. Germany, however, steeped in cultural activity, with over 60 dance companies in municipal and state theatres and opera houses as well as hundreds of freelance groups, is the most active “dance landscape” in the world, with auditions to be found even in the remotest of towns.

As it is near impossible to provide an overview of the entire European dance scene, this article focuses on Germany. Any dancer on the European audition trail is bound to wind up in this country, and although some renowned dance companies immediately spring to mind, it may also prove wise to get off the well-beaten track.

Three authoritative voices with a mutual connection to the Stadttheater (municipal theatre) in Augsburg (pictured main), a Bavarian city north of Munich, were generous enough to share their experiences and advice with Dance Australia readers: Robert Conn, who is a former Stuttgart Ballet dancer and director of the Ballett Augsburg, Alisha Coon, who was previously in the Ballett Augsburg ensemble and recently retired from dancing after returning to Australia in 2012 to join the Sydney Dance Company, and Joel Di Stefano, an Australian Ballet School graduate who moved to Augsburg in 2012.

By first addressing the most glaring questions hopefully those preparing for an audition tour will feel better equipped to begin their own research:

What is a municipal theatre? How do they operate? What do they offer? Where do they advertise? Which positions could you possibly fill?

Augsburg’s Stadttheater is typical of many German theatres and comprises four divisions: an actors’ theatre, opera and musical theatre, a philharmonic orchestra and a ballet company.

The city is comparable in terms of population and area to Newcastle in NSW and its theatre dates back to 1777. Some dance companies have been forced to close in recent years, mainly due to austerity measures which have affected the arts around the world. Nevertheless, Augsburg has maintained its dance loving tradition and plays host to a repertory company of 16 dancers.

Since director Robert Conn took the helm seven years ago the company has performed works from 44 choreographers.

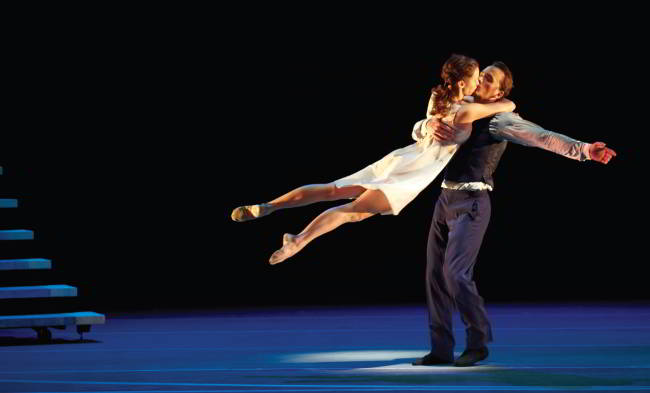

“I didn’t know anything about Augsburg before I lived there,” Alisha Coon (left, performing Mauro De Candia's Cinderalla with Patrick Howell) says candidly. “It’s quite normal not to know much about a city because it’s the company you’re interested in. Augsburg was building a reputation for having great guest choreographers working with the company all year round.”

“I didn’t know anything about Augsburg before I lived there,” Alisha Coon (left, performing Mauro De Candia's Cinderalla with Patrick Howell) says candidly. “It’s quite normal not to know much about a city because it’s the company you’re interested in. Augsburg was building a reputation for having great guest choreographers working with the company all year round.”

While it often pays to research the city as well as the company, especially in the case of former socialist concrete jungles or “dying” industrial boom towns, Conn expects dancers to do research of a different kind. “Only one in 10 comes prepared to an audition,” he says. The rest are merely “unarmed and knocking on the wrong doors”.

When the audition comes down to a small group of finalists, it pays to know “what you’re applying for, especially in an interview. Put yourself in the feet of the director, know about the position and what his vision is”.

When a dancer isn’t familiar with the company’s repertory or structure, doors tend to close. In an attempt to console the dancers he chooses not to employ, Conn often asks out of interest, “Where are you going next?” But more often than not he’s left scratching his head: “If you’re picking that, why did you pick me?”

Sixty kilometres to the south of Augsburg are two more dance companies based in Munich – the world renowned company of the Bayerische Staatsoper and a contemporary dance company resident at the Staatstheater am Gärtnerplatz. Sixty kilometres to the west of Augsburg is another dance company in the university town of Ulm.

In the Rhine-Ruhr region, an area considerably smaller than metropolitan Sydney, there are a total of six theatres housing dance companies and approximately 80 freelance/project-based contemporary dance groups! When organising an audition tour it may just be worth considering in advance: should I travel an hour in the other direction instead?

So where does one begin to look? During her time in the Queensland Ballet Professional Year, Coon “was lucky to be able to ask the company dancers for advice about companies in Europe. I also found the Dance Europe audition website very useful.” Conn also confirms that the only audition listing he posts is in Dance Europe magazine.

Various websites repost audition notices, such as tanznetz.de, a German language online community which is a handy resource for auditions and reviews. Dance Germany (dance-germany.org) also provides a comprehensive list of all German “civic companies,” a bizarre translation which simply refers to dance companies in publicly funded theatres.

Di Stefano had a less methodical approach and “found out a lot from directors, dancers and other people who were auditioning”.

This year, Con n’s audition notice attracted 1200 applicants, a number which has been growing from year to year. Of these 1200, a hundred tend to get invitations. Although he invites 100 dancers, Conn (left) must account for a small percentage of dancers who cancel, in addition to “no shows”.

n’s audition notice attracted 1200 applicants, a number which has been growing from year to year. Of these 1200, a hundred tend to get invitations. Although he invites 100 dancers, Conn (left) must account for a small percentage of dancers who cancel, in addition to “no shows”.

He also warns bitterly, “Don’t apply, say you’re going to come and not come,” assuring me that dreaded “black lists” do exist.

In light of how few dancers receive an invitation to an audition, the initial correspondence with a director should be taken very seriously. Conn explains that as part of the selection process he personally spends approximately five minutes considering each application – surprising considering most directors relinquish such tasks to their staff and interns.

Although basics such as height, weight and “pedigree” are the first points to be scrutinised, there are other criteria. “A dancer who sends me a barefoot picture jumping on the beach doesn’t know what they’re dealing with,” he states sarcastically.

Perhaps not as shameful, but equally suspicious, are dancers in their mid-20s submitting photos of themselves at the barre as opposed to publicity photos taken on stage.

With regard to show reels: “It doesn’t do anybody any good to say, look at the dancer third from the left at two minutes, or send excerpts from 40 ballets cut to pop music. A total of three-and-a-half minutes tops that parallel with the repertory of the company” are more than sufficient.

Generic e-mails with many recipients, i.e. “Dear Director” group emails, are a common faux-pas often accompanied by links to a résumé, photos and videos. Although impersonality is generally enough of a deterrent, Conn points out that links to third party hosts such as Flickr or Dropbox are a time consuming inconvenience. “Links? I don’t open them.”

There is a dominant notion among dancers that success is more likely at so-called “private auditions.” Alisha Coon argues in favour of them, explaining that she tended to have more luck with private auditions.

“In open auditions you are a ‘number’ among hundreds of other dancers.” By auditioning with the company dancers on a regular work day, she argues that auditionees are guaranteed the “director will see you and most of the time have a chat with you.”

It offers a chance to get personal feedback and “establish connections for future job opportunities.”

Di Stefano (left, with Yvonne Compagna Martos) also found that private auditions allowed him to “get a good sense of the company, its dancers and whether I was well-suited.” However he admits: “Interestingly, I got my job in Augsburg through an open audition.”

Di Stefano (left, with Yvonne Compagna Martos) also found that private auditions allowed him to “get a good sense of the company, its dancers and whether I was well-suited.” However he admits: “Interestingly, I got my job in Augsburg through an open audition.”

Conn on the other hand finds them problematic. “Private auditions are a far weaker way of auditioning. Public auditions are planned to see and test certain things.”

Although many dancers benefit from reduced stress levels, Conn believes “company class is not ideal [for an audition] because the company dancers couldn’t give a damn, and I don’t have time to work personally with them and see how quickly they learn.”

Needless to say, coordinating auditions and travel is a difficult task in itself; Di Stefano confides that he received his job offer after a total of 10 auditions, a rather modest number which many auditionees exceed in a matter of weeks!

“Negotiate with the director,” he advises, supposing clashing auditions or previous commitments and performances cause planning problems.

Unlike companies in most English-speaking countries, which have no other choice but to fundraise and present works which attract a generous paying audience, German theatres aim to educate and engage the broader general public. They also provide artists with the chance to pursue their own vision without the sale of tickets lingering at the fore.

Conn appreciates the socially oriented, not-for-profit structure of municipal theatres as it enables him to plan ahead, without the threat of booms or crashes. Regardless of the increasing success of his company, the working conditions and company’s budget will not change.

In Augsburg three dance productions are staged per season and a fourth production is created in cooperation with another department of the theatre, such as the musical theatre department. The program is then rounded off with an international gala and an occasional choreographic evening.

“Sometimes we got to do great co-productions,” reminisces Coon, though sometimes the experience was “not so fun,” performing “three-hour long operas where we would only dance for 20 minutes!”

Di Stefano appears to have been spared the pain of lengthy opera productions, describing the “opportunity to get to know and work with the actors, opera singers and musicians” as a highlight of theatre life.

Like in most German theatres, 10 to 14 performances of each production are spread over the entire season.

This article has described the basic features of European theatres using Augsburg as a starting point. The cultural and political differences between each European country have been largely overlooked in favour of a more universal view.

It should be acknowledged, however, that political aspects do play a significant role. In the Netherlands, for example, non-European citizens are at a significant disadvantage when applying for a position, something which severely impacts most Australian dancers’ chances.

Nevertheless, a small amount of research offers much needed reassurance and the ability to assess which job could be the right one for you!

DO:

• Put effort into email writing; a badly written email could be costly.

• Find out if there are other companies are in the area you’re travelling to, as you might have chosen to audition at the wrong one!

• Research the company’s style and repertory. Interviewing finalists is standard practice and you want to show you’re interested and informed.

• Keep your résumé concise. Companies spend only a short time reading each application and summer workshops and childhood exam results are more often than not ignored.

• Consider the size of the company. Smaller companies require all dancers to be able to dance soloist roles.

• If you’re interested in a particular company, read the dancers’ biographies online and keep an eye out for any attributes they have in common. For instance, a company that performs contemporary repertory might only employ dancers with a strictly classical background. Conversely, a “Ballett” company may not have any balletic dancers in its ranks!

DON'T:

• Apply before doing some research and considering if you’re an appropriate candidate. Travel and accommodation costs add up quickly!

• Presume that private auditions are the only means to success. Your strength may lie in learning repertory quickly, or pas de deux, talents best presented at a public audition. Auditioning privately on a company’s regular working day limits the time a director can spend working with you without disturbing the day’s schedule.

• Send classroom photos. Photos of academic poses rather than of stage performances creates an impression of inexperience.

• Take no answer for an answer. Competition is tough and a short phone call, especially if you’re in the running for a position, could be the reminder a director needs.

• Send a show reel unless you have quality recordings of yourself in a soloist role, or footage is specifically requested.

• Be overambitious. Smaller companies are a great stepping stone for young dancers.

Luke Aaron Forbes attended the Victorian College of the Arts Secondary School and completed his dance training at the École-Atelier Rudra-Béjart in Lausanne. He has danced with Béjart Ballet Lausanne, Ballett Dortmund and Aalto Ballett Theater Essen, both in Germany, He is now studying a Master of Arts Tanzwissenschaft (German Dance Studies) at the Hochschule für Musik und Tanz in Cologne.

This article was first published in the June/July 2014 issue of Dance Australia magazine.

See more photos of Alisha Coon and Joel di Stefano on our app!