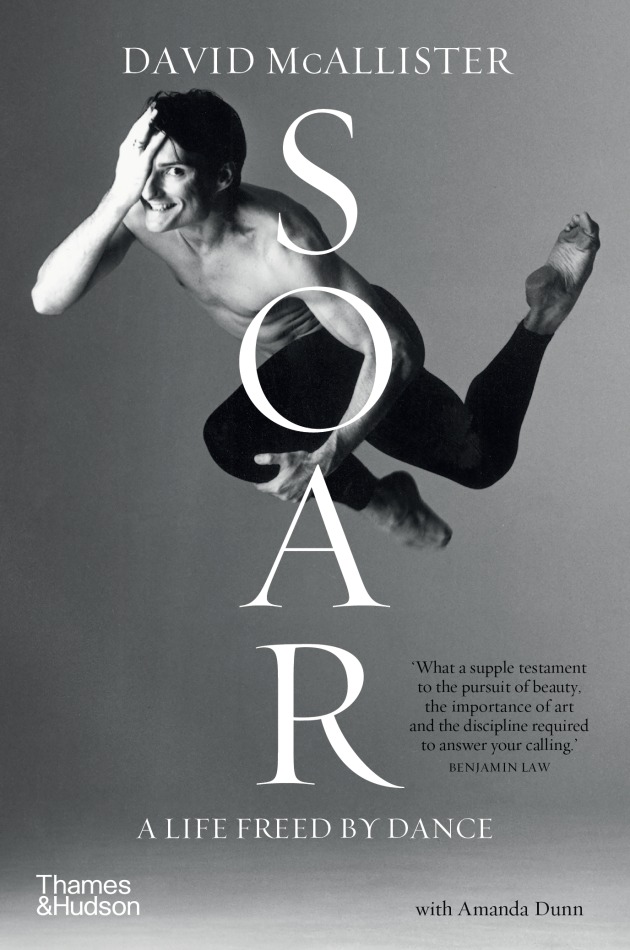

Review: 'Soar, A life freed by dance', by David McAllister

The outgoing artistic director of the Australian Ballet has written a book looking back over his long ballet life.

David McAllister’s whole life has been the Australian Ballet (AB) – he trained at the school, danced with the company for 18 years, and became its longest-serving artist director. Now, after having held one of the country’s most glamorous jobs for 20 years, he has decided to step down. Soar, a life freed by dance is his farewell autobiography.

So it is quite a surprise when his Introduction doesn’t begin with ballet but instead with his first sexual experience. In this way he immediately establishes that Soar is not just about his career but also about his long coming-to-terms with his sexuality.

At age 19 McAllister met and began a relationship with his idol, 37-year-old Kelvin Coe, the AB’s principal dancer. (Coe was a celebrated dancer who was much later exposed against his will by a journalist as one of the first public figures in Australia of having AIDS, of which he died in 1992.) This encounter awakened McAllister’s nascent sexuality and the pair became casual lovers, but he did not face the fact that he was gay until a good 20 years later. In between he had a number of fulfilling relationships with women, in particular Elizabeth Toohey – in fact he was devastated when she called off the romance. Yet, on the evidence of this book, he seems to have been so deeply consumed by his first love – ballet – and found so much emotional fulfilment from his career, that his romantic life took second place.

After this surprise curtain raiser, McAllister begins at the beginning, describing his childhood in suburban Perth, dancing in front of his reflection in the TV. His was a happy, churchgoing family with three siblings. He was a mischievous, funny, wilful child, a born show-off. He begged to learn ballet at age seven after seeing Nureyev in a snippet from the AB film of Don Quixote on TV. “It was like a bolt of lightning had struck me,” he writes.

Thereby begins a familiar story for many boys learning ballet – being the only boy in a class of girls and the awful agony of schoolyard bullying. He describes it with a light touch, but the “poofter” taunts stayed with him for life and were a major reason for his self-denial. He did not want to be what the bullies had always labelled him to be.

From the start of his ballet obsession he was focused on joining the Australian Ballet. He auditioned successfully for the school but his parents would not allow him to join until a year later, in 1981, after he had finished his HSC. His focus did not waver. After having been hauled in for some filler spots in Spartacus, he found himself in the company by 1983.

He arrived just as the company was still recovering from an industrial strike and at the start of Maina Gielgud’s appointment as artistic director. It was a time of flux. According to McAllister, she dismantled the prevailing hierarchical structure, giving roles out according to her preference rather than rank, and had an informal approach to management, preferring to be addressed by her Christian name.

Gielgud was in charge for 13 years, and her reign ended amid much controversy. By then, many dancers had departed the company and Gielgud’s management was in question, but McAllister does not go into these overarching issues. Perhaps, as a rookie dancer concentrating on his own personal advancement, he was not aware of the bigger picture. The reader does get a glimpse, however, of the careless management style – not necessarily of Gielgud’s but common for the time – offhand remarks that could crush a dancer’s feelings, the pressure to be thin and to perform despite injury, the casual criticism. Gielgud added to McAllister’s self-consciousness by telling him he should get a nose job and that he was too short to ever perform prince roles – i.e. be a principal dancer.

At 21 he and Toohey began his first “normal” relationship (much to his relief). Their mutual joy in each other reflected in their sparkling on-stage partnership. In 1985 Gielgud chose them to compete in the 5th International Ballet Competition in Moscow, “the Olympics of the ballet world”. Coe went along as their coach. McAllister won a Bronze Medal and Toohey a “special award for artistic merit”. They became the toast of Russia and Australia, and were invited back four times for guest appearances – unusual in those Soviet years. Despite this triumph, Gielgud still did not promote McAllister to “prince” until she discovered he was on the verge of leaving to find a more satisfying post overseas.

Having now finally reached top rank, McAllister enjoyed more thrilling experiences, including meeting Princess Diana in a special gala performance in the UK. He also suffered a run of injuries – ankle, knee and back. The enforced rest gave him time to face up to his attraction to men.

With the arrival of Ross Stretton in 1996, “we [the company] felt like we’d gone from high school to university overnight”. Stretton brought in a more American model of directorship and was much more distant with the dancers. He felt the company had been “stuck in its ways” and was determined “to bring in more contemporary works”. McAllister, who was 34 by this stage, was nervous that Stretton might “suggest I move along”, but instead was pleasantly surprised to find him “extremely supportive”, casting him in all the principal roles. He went on to have one of the most productive periods of his dancing life.

Just as McAllister was staring into the “abyss of life after dancing”, Stretton was appointed to the Royal Ballet and the top job at the Australian Ballet was suddenly up for grabs. With the encouragement of former administrator Noel Pelly, McAllister applied.

His appointment to the post was widely seen as a bit of a gamble. He himself admits he “hadn’t run a chook raffle”. Was he was too inexperienced, too close to the dancers, too nice to make the tough decisions? “As always, I was determined to prove the doubters wrong,” he writes. He admits that he was naive in hoping to create a ballet “nirvana”, writing that he still struggles to this day with giving his dancers bad news. He emerged “shellshocked” from some of his first salary negotiations. He also writes that his “deep love of pleasing people had been a double-edged sword”, such that he did not “push back” hard enough at times against the financial caution of the board, with some “potentially great works” having been shelved as a result. One longs to know what they were.

Nonetheless, his legacy is honorable. He is aware of the criticism that his programming has been too “safe”, but believes he has not been given enough credit for his achievements. He scored a coup with the commission of Graeme Murphy’s Swan Lake, brought in John Neumeier’s Nijinsky and commissioned innovative choreographers like Wayne McGregor. He honoured the past with the three-year Ballet Russes project, and the future with the in-house choreographic season, Bodytorque.

He takes pride in having cultivated rising talent, and pays tribute to his many collaborators. He lists among his achievements the opening up of the company from its closed, elitist image, the introduction of generous maternity leave, the world-leading conditioning and strengthening program, a new body image policy, the Education Program and the increasing racial diversity of his dancers.

Meanwhile, what of his sexuality? McAllister continued to see men for casual sex, but it was not until he met the right person, theatre director Wesley Enoch, that he felt ready to settle into an open and committed relationship with a man. Remarkably, although his younger brother had already “come out” as gay, McAllister did not formally “come out” to his family until 2008, when he was 46 years old.

McAllister’s tone is light, friendly and always fair. This is not a book of scuttlebutt and gossip. McAllister’s exuberant dancing and his love of the artform were infectious; he has given much joy to the world. Now he steps into another phase of his career, with the man he loves by his side.

Soar had been timed to launch with farewell galas – one in Melbourne and one in December at the end of the year. Time will see if these go ahead.

- KAREN VAN ULZEN

'Dance Australia' has TEN copies of 'Soar' to GIVE AWAY! Just enter here.

‘Soar: a life freed by dance’, by David McAllister (with Amanda Dunn), Thames and Hudson, paperback, $39.99. Available from October 1. https://thamesandhudson.com.au/product/soar-a-life-freed-by-dance/