Compagnie Par Terre/Anne Nguyen Kata.

Space Theatre, Adelaide Festival Centre

October 18

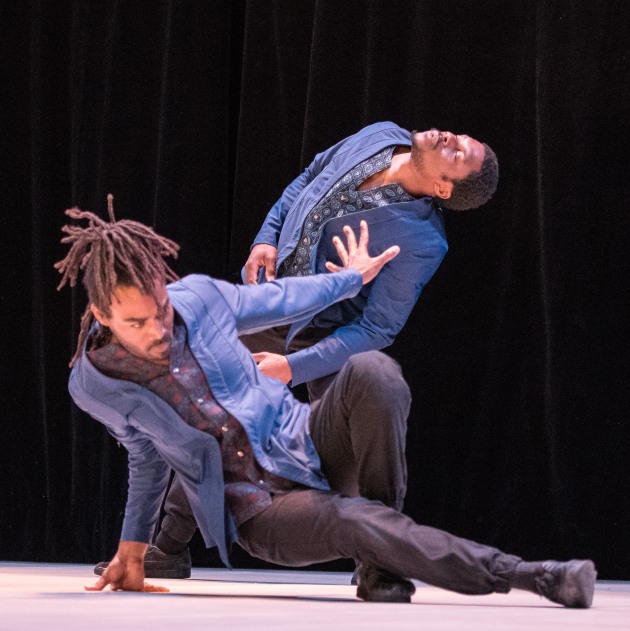

Compagnie Hervé Koubi. What the Day Owes to the Night

Dunstan Playhouse, Adelaide Festival Centre,

October 23

This year’s OzAsia Festival continues the strong dance programming that has been a welcome feature of Joseph Mitchell’s directorship. Damien Jalet’s Vessel, which was given ecstatic reviews at the 2018 Perth Festival, was an astonishing fusion of dance and art installation (see here). The two works reviewed here, Anne Nguyen’s Kata and Compagnie Hervé Koubi’s What the Day Owes to the Night, are notable for both drawing on various forms of street dance.

French-Vietnamese choreographer Anne Nguyen studied gymnastics and martial arts before discovering breakdance, and her work references and blends these forms with hip hop. Kata, which premiered in 2017, features six male and two female dancers, who are clothed in stylized jackets and pants.

The work opens to a bare stage illuminated by a single down light, as the percussive score by Sébastien Lété starts. A single male dancer performs a sequence of virtuosic breakdance spins, precariously balanced on head and hands. Other dancers enter and a series of ‘battles’ ensues in which dancers run at each other as if to make contact and fight, but stop short. Using martial arts moves they engage in imaginary combat, ducking and weaving around each other with alternating attacking and defensive movements. Various group formations follow, in some of which bodily contact is made.

Much use is made of the glance, with long periods of immobility in which the dancers eyeball each other, sometimes combatively and sometimes in a more seductive vein, whilst at other times the glance is projected into the wings as if to an adversary waiting there. Towards the end of the hour long piece there is an extended sequence in which the dancers side step across the stage from left to right, assuming stances borrowed from boxing and bull fighting. To my mind this sequence went on too long, and the work could have been shortened by a third: however, the audience reception was very enthusiastic.

Before the curtain went up on What the Day Owes to the Night French-Algerian choreographer Hervé Koubi gave a speech about the work’s origins. In halting English, Koubi recounted his surprise at being shown a photo of his Algerian great-grandfather wearing flowing Arabic robes, prompting a trip to Algeria to discover his roots. In Algeria he worked with a group of 13 male street dancers, most whom are self-taught in disciplines ranging from martial arts and capoeira to hip-hop. Together they created What the Day Owes to the Night.

The work starts in languorous fashion, with the men lying in sculptural heaps on the floor in semi-darkness. Hand are raised slowly to the sky before they gradually rise to their feet. Lionel Buzonie’s subtle lighting softly illuminates their extraordinarily muscular, bronzed torsos, which are equally well complemented by flowing white pants. Guillaume Gabriel is credited with both costumes and sound; the score is a rich mixture of snatches of Bach, Sufi trance music, bells and solo Algerian instruments I cannot identify.

The movement oscillates between the slow and sculptural and the frenetically acrobatic. The performers create human mountains, over which one of them leaps; they gather together to throw one of their number horizontally into the sky; they perform endlessly inventive series of flips and tumbles. Despite this athleticism, the work is infused with an almost mystical sense of ritual as these movements are interspersed with sculptural formations, often with the dancers’ very eloquent backs turned to the audience. A recurrent motif of prolonged spins on the head, in which they use their hands to aid turning, calls to mind upended Swirling Dervishes as well as ballet’s set piece of the thirty-two fouettés, albeit done upside down.

When the end comes, the fraternal feeling that suffuses the work is amplified as they link hands together in a chain, stomping their feet, with one dancer breaking into spoken Arabic. In a final moment of stillness, they once again raise their arms to the sky. This is an extraordinary work, performed by a stupendously athletic group of dancers who together create moments of great beauty.

- MAGGIE TONKIN